“The Philadelphia Experiment” The Movies

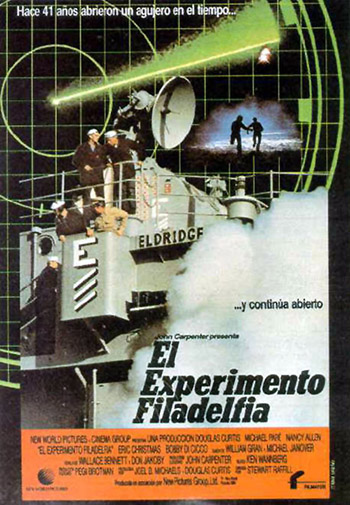

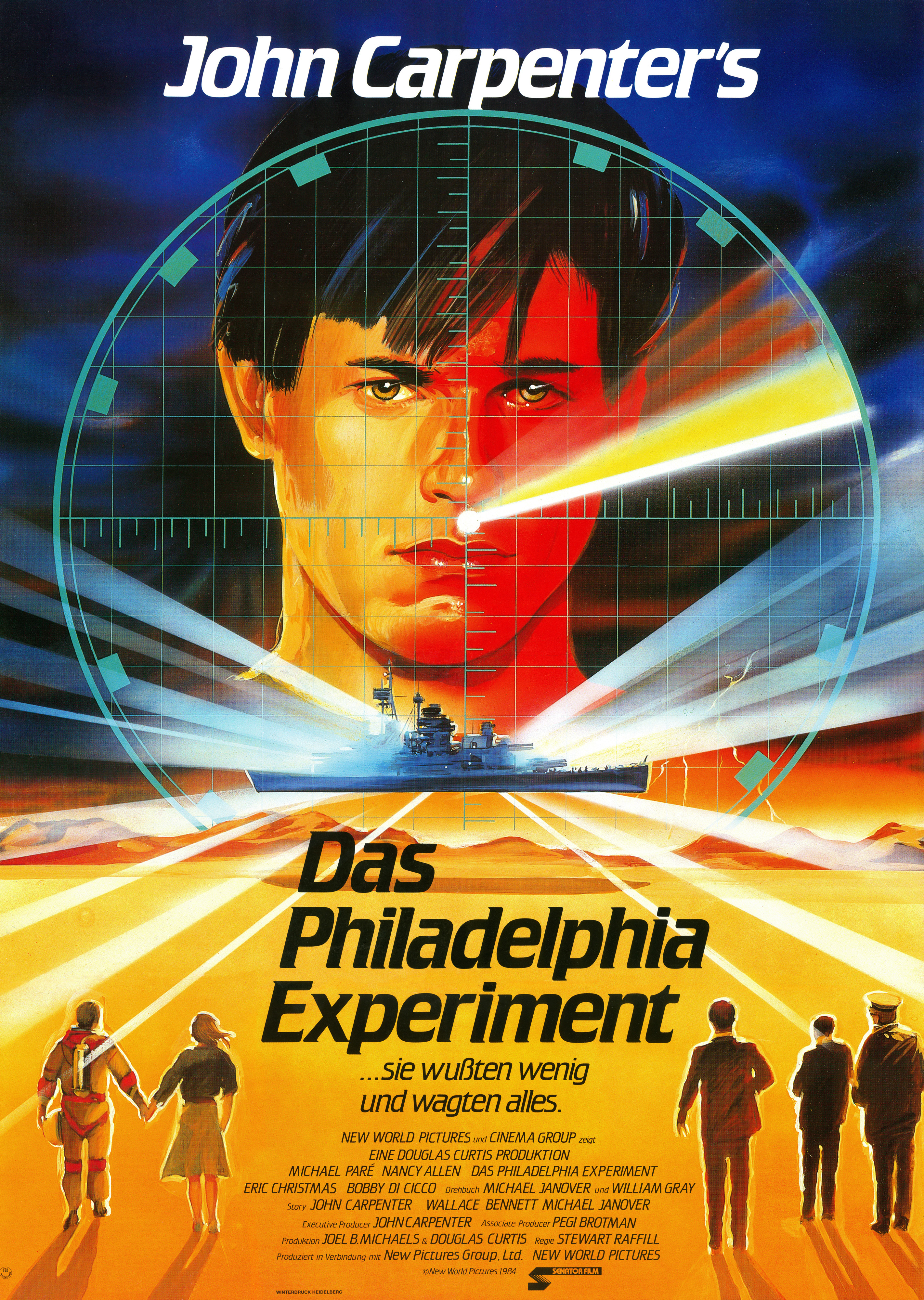

The Philadelphia Experiment is a 1984 science fiction film. It was directed by Stewart Raffill and stars Michael Paré, Bobby Di Cicco, and Nancy Allen. The movie is set in 1943 where two sailors, David Herdeg (Paré) and Jim Parker (Di Cicco), are stationed on the USS Eldrige used for an experiment to make it invisible to radar. However, the experiment goes horribly wrong and the ship completely disappears and Herdeg and Parker find themselves in the Nevada desert in the year 1984. They find out the program has been revived in 1984, unexpectedly interacting with the experiment in 1943 and putting the entire world in danger.

“Reportedly based on a true incident during World War II involving an anti-radar experiment that caused a navel battleship to disappear in Virginia…” 3½ Stars [1]

It was this science fiction film that first caught my interest in the Philadelphia Experiment, and to this day is still widely available on DVD.

As it turns out there were two movies entitled “The Philadelphia Experiment,” produced by Doug Curtis. One in 1983 and in 1993 a squeal was released, “The Philadelphia Experiment II”, which deals with Germans running amok in time:

“In our story {Philadelphia Exp. 1I} the Germans don’t care about altering history, because they have no sense of what the history is, they’re trying to win the war. So they learn how to fly a stealth bomber in a matter of days and they bomb Washington, and suddenly history is changed.” – Doug Curtis Producer of “The Philadelphia Experiment {1 & II}” [2]

Most people are more familiar with the first version produced in 1983 involving the Eldridge:

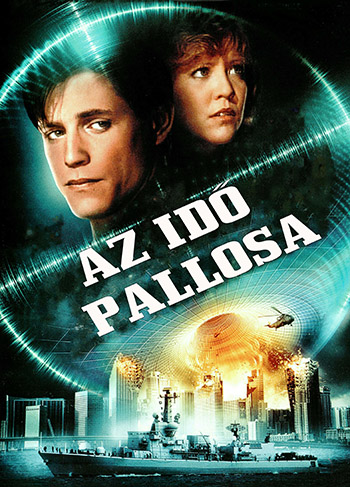

“The premise is very… relatively simple, I’m not sure if you know the original Philadelphia Experiment {referring to the first movie}, but it was essentially about things moving through time vortexes, some people came forward from the 40’s to the early 80’s when the movie was originally made. The concept I had and introduced into the script is really to do with alternate realities.” – Steven Carnwell Director of “The Philadelphia Experiment {2}”, Produced by Thorn EMI Video in 1983. [3]

“This now, this time, it’s not ours. We weren’t here when it happened. The experiment took place on a ship in a Philadelphia harbor. It was – 1943, October. Does this sound… crazy? You know, or is this sort of thing possible now?” – David Herdeg (The Philadelphia Experiment Movie)

Some of the new “witnesses” have said the government tried to ban the first movie from being shown in the U.S. Why would the government ban a science fiction movie, when doing so would only serve to make it more believable than simply letting it run and saying “it’s only a movie….” or, did they really ban it?

Upon checking newspapers around the time the film was released nothing was amiss, as various newspapers around North America ran reviews as usual:

- Published on August 3, 1984 in The Washington Post “’Experiment’: Time Tripping”

- Published on August 9, 1984, in The Washington Post “Failed ‘Experiment’”

- Published on August 24, 1984 in The Philadelphia Inquirer “THE PHILADELPHIA EXPERIMENT’ TAKES A TIME TRIP”

- Published on August 27, 1984 in the Philadelphia Daily News “PHILADELPHIA EXPERIMENT’ A FILM WHOSE TIME HAS COME”

- Published on August 24, 1984 in the Beaver County Times “‘Philadelphia Experiment’ is an experiment that fails”

- Published on August 26, 1984 in the Star News “‘Philadelphia Experiment’ becomes invisible fast”

it went on to win a few awards; Winner – Best Science Fiction Rome International Film Festival, and Fantafestival Award for Best Film in 1985. In no way was it looking like a “Banned film”

The PX legend as told (before Bielek) concerns two events: Invisibility and Teleportation. There is no account at all of time travel. Steven Carnwell (Director of the “Philadelphia Experiment”) says that he added the idea of alternate realities / time travel to enhance the movie’s storyline.

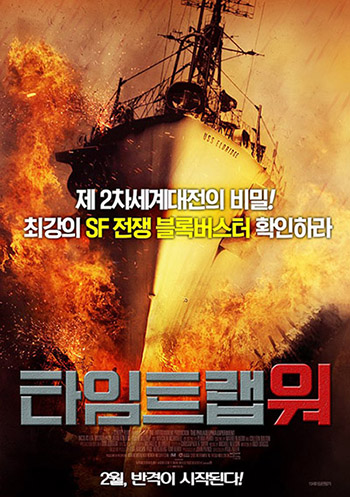

In 2012 The Sci-Fi Network produced a made for TV squeal of the “The Philadelphia Experiment”;

Cast of The Philadelphia Experiment;

Michael Paré as David Herdeg

Nancy Allen as Allison Hayes

Eric Christmas as Dr. James Longstreet

Bobby Di Cicco as Jim Parker

Louise Latham as Pamela

Stephen Tobolowsky as Barney

Ralph Manza as Older Jim

Kene Holliday as Major Clark

Joe Dorsey as Sheriff Bates

Michael Currie as Magnussen

Gary Brockette as Adjutant / Andrews

Debra Troyer as Young Pamela

Miles McNamara as Young Longstreet

James Edgcomb as Officer Boyer

Glenn Morshower as Mechanic

Length: 1 hr 42 min (102 min)

Release Date: 3 August 1984 (USA)

Budget: $21,000,000 (Estimated)

“In ‘The Philadelphia Experiment’, a secret government research project tries reviving the World War II “Philadelphia Experiment,” which was an attempt to create a cloaking device to render warships invisible. When the experiment succeeds, it brings back the original ship (the Eldridge) that disappeared during the first test in 1943 – which brings death and destruction to the 21st century. It’s up to the sole survivor (Lea) of the first experiment and his granddaughter (Ullerup) to stop it.” – SyFy Official Press Release

The Philadelphia Experiment (1984)

The Philadelphia Experiment II

The Philadelphia Experiment (2012)

David J. Halperin’s gives some nice background; (You can read David’s full article, the following is reprinted with permission)

Gray Barker—who died the year of the film’s release, who may or may not have seen it before his death—knew about it while it was in the works. He speaks of it in a letter, dated 9 December 1981, to “Carlos Miguel Cristophero Allende, General Delivery, Pecos, NM.” This letter, and the one from Allen to which it obviously replies, are worth quotation here. Not least for what they convey about Allen’s relations with the people who got rich, or would have liked to have gotten rich, off his manic creativity.

“Dear Carlos,” Barker writes. “Thank you not only for your latest letter concerning Mr. Moore, but for all your other missives, especially the annotated edition of THE PHILADELPHIA EXPERIMENT by Moore/Berlitz, which set some of the record straight.

“I cannot see why Mr. Moore would harass you, especially when your person was one of the most popular and amazing parts of the book. I have followed your Maritime career previously and have been aware of your rapid promotion which indicates a superior mind. Even that Mr. Goerman, who wrote the unfavorable article for FATE, admitted that you appeared to be a genuis [sic] or near genius while in school in Pennsylvania.”

Barker writes that he’s enclosing a copy of Anna Genzlinger’s book The Jessup Dimension, for Allen’s comment. “You will note that Ms Genzlinger has ‘translated’ your Allende Letters to Jessup. By ‘translated’ I mean how she has taken the formal and technical language of the original and put it in more popular idiom that the lay person can fully understand. I do hope this permits more readers [to] understand the many important points you were making in those letters. Although I do not question your scienfific [sic] knowledge, I think that you sometimes have a communications problem. Because your mind moves so swiftly, you assume that the minds of your readers can keep up with yours. In your refusing to ‘talk down’ to your public, there is much valuable information they miss which you otherwise could impart if you would [use] less technical language and a more informal approach. …

“I read in a recent VARIETY (the show business weekly) that Avco Embassy pictures will begin making a picture entitled THE PHILADELPHIA EXPERIMENT very shortly, though I do not know if it is based on the Moore/Berlitz book. About one year ago two researchers employed by 20th Century Fox Studios called me from Washington, D.C. where they were researching the Philadelphia Experiment, evidently with the thought of making a picture about it. They wished to get in touch with you, but at that time I had no idea how to contact you, so I sent them to Mr. Goerman, feeling he might be able to get word to you through your parents. I was hoping that you might be able to turn some greenbacks by acting as a paid consultant for them.

“Again, thank you for your many kindnesses in sending me various informative letters and materials. While I have not been able to fully undertand [sic] the scientific and technical aspects (my education is in the Humanities), I have filed all of these carefully away, and will eventually donate these to some University, along with other correspondence files.”

Of course Barker’s poking fun at Allen; he’s been doing that from the beginning of the letter. Yet there’s real kindness here, from a man adept at “turning some greenbacks” to another man whose threadbare, peripatetic life suggests he could have used some help in that direction.

It’s interesting, too, given the distance the “Philadelphia Experiment” movie was to travel from the legends of which it was begotten, that the master greenback-turners of Hollywood thought it worthwhile to seek out the fountainhead of the legends. Would they really have put him on their payroll, I wonder?

Moore, thanks to Allen, already had his best-seller. Between him, and the penniless wanderer whose mythmaking had made both book and movie possible—to whom shall we give our sympathies?