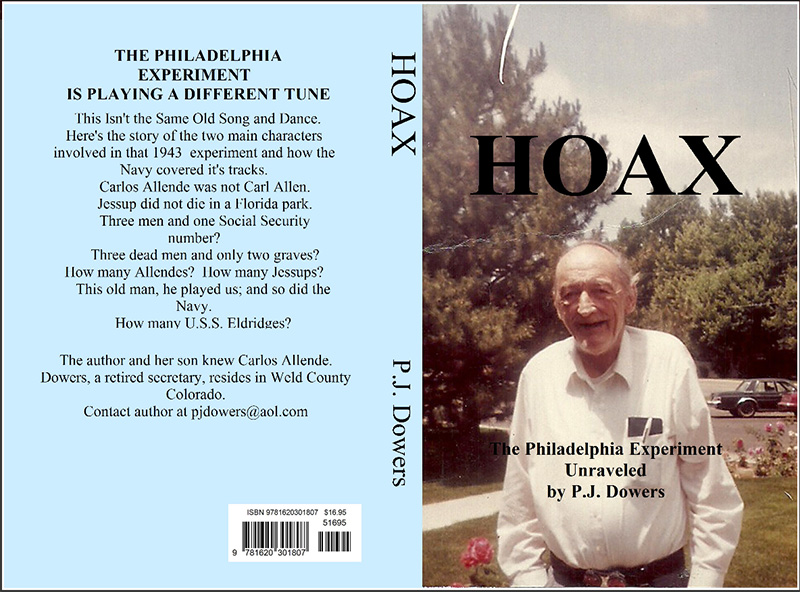

Review of “Hoax: The Philadelphia Experiment Unraveled“, by P.J. Dowers. Pandora’s Press, 2012. Available for $15.95 from TheBookPatch.com

Hoax is an odd title for a book so committed to the reality of the Philadelphia Experiment–invisibility, teleportation, and all. This is a rather odd book in general, and at times maddening. Yet it’s a book that leaves a good taste after it’s finished, it’s so plainly honest and heartfelt. Written by a woman who befriended Carl Allen in his last years, it’s less about the Experiment than about its creator, the strange and lonely nomad who’s found a kind of immortality as “Carlos Allende,” the author of the “Allende letters.” Its fundamental message: There was more to this old man than met the eye! It deserves to be read, not for its farfetched conjectures about what that “more” was, but for its passionate advocacy of this real and essential truth.

First, the author. Her name is not, as the book claims, Phyllis Dowers. That is evidently a pseudonym, used (I would imagine) out of fear that powerful and sinister agencies will take revenge on her for having written it. It seems to me certain she’s identical with the “Phyllis,” with a very different surname, who in September 1995 wrote a postcard to David Houchin, curator of the Gray Barker Collection in Clarksburg, West Virginia, informing him of Allende’s death and announcing her intent to write a book In Defense of Carlos. This is plainly the book she’s now published. I wish she had kept her original title. It conveys far better than Hoax what the book is about.

She speaks about herself only incidentally, in bits and pieces. We learn she’s a long-divorced mother of eight, two boys and six girls; two of her daughters have worked at the Centennial Health Care Center in Greeley, Colorado, where Allende spent the last eight years of his life. She’s far from wealthy, and burdened with a special tragedy: two of her children died within two months of each other, at the end of 2002 and the beginning of 2003. One of these was her son Ray, to whose memory the book is dedicated, and whose remembered conversations with her on the subject of Carlos and the Experiment fill many of its pages.

There’s a particularly poignant passage in the seventh chapter. At her final meeting with Allende, in the fall of 1993–he died on March 5, 1994–Phyllis tells him she wants to tell his story. “I want it told too, Phyllis,” he answers. “I want it told like I tell it, not with everything all garbled up. … You’ll have to wait, but write it down so you don’t forget.” She needs to wait, he says, because certain people, including her and Ray, could be hurt. He’s earlier told her to wait until after his death, fifteen or twenty years; and at the end of the chapter, after they’ve said their goodbyes, she tells Ray: “Well, Son … I’m fifty-seven years old. I may not be here in twenty years. You may have to write that book.” But twenty years later Phyllis was still around to write the book. It was Ray who was dead.

The Carlos Allende who appears on Phyllis’s pages is a different man from the one I knew through my researches in the Gray Barker Collection, which I’ve blogged about here extensively (and summarized in my essay on the Philadelphia Experiment for The Revealer). Gone is the solitary, embittered wanderer, pouring out his deprivation and rage in one futile letter after another. Instead we meet, in June of 1991 at the Centennial Health Care Center, a man in his sixties who looks more like 90, yet who’s charming enough “to melt the rivets right off a female’s jeans” (p. 15). A genial raconteur, he captivates Phyllis with his reminiscences of Albert Einstein, who taught him physics in a dizzying week and a half of evening tutorial sessions (“He was fun to be around, a real character“), and his tales of burying the invisible corpse of an invisible sailor. (Named David; I suspect here the influence of the “Philadelphia Experiment” movie.) “That was all the burial I could give that pioneer of star travel, just the beauty of the park for his grave. I knew the dogs would smell him, and tear and eat his flesh, but there wasn’t anything I could do about that” (p. 47).

What a crock! is Phyllis’s initial response. But soon she’s fallen under the old man’s spell. “You’re kind of a scamp, aren’t you?” she tells him, giggling (p. 37). Meanwhile her son Ray becomes so fascinated with Allende that he follows him in his car to see where he’s going–not unnoticed by Carlos, who weaves this into a story of his persecution by mysterious agencies. “‘Keep these for me, Amigo.’ Carlos slipped the envelope from under his arm and handed it to Ray as they seated themselves with their food. ‘Lest my copies be stolen,’ he added to Ray’s raised eyebrows. ‘Someone’s been tailing me.’” (p. 59).

Food. (On this occasion at a Western Sizzlin’, where Ray has taken him to lunch.) When I last spotted Carlos in the files of the Gray Barker Collection, he was chronically malnourished, “starving … except in summer when food is easily stolen.” Not anymore. The chief relic of his years of hunger is his inability to control himself in the presence of mashed potatoes. “Lilly [Phyllis’s daughter, a nurse’s aide at Centennial] remembered how he’d dig into a mound of mashed potatoes and shove huge forkfuls into his mouth. ‘He couldn’t get enough potatoes. He was not quite the gentleman then,’ she laughed. Oh, but how he could flatter the ladies; he loved blond hair, he told Lilly, and asked her to marry him” (p. 205).

The turning point obviously comes in the summer of 1986, when Allende arrives in Greeley and takes up residence at the Centennial. (“The girls here spoil me,” he remarks to Phyllis, as an aide brings him a refreshing drink on a warm day.) This is the point at which the flood of letters from him in the Barker Collection entirely dries up, presumably as an effect of Barker’s death at the end of 1984. On August 22, 1986, The News of Colorado Centennial Country runs a huge feature article on him, under headlines like Mystery man offers death bed statement and Allende trained by Einstein on invisibility theory. A sequel, the week after, is headlined Allende was Colonel in Polish Home Army.

The turning point obviously comes in the summer of 1986, when Allende arrives in Greeley and takes up residence at the Centennial. (“The girls here spoil me,” he remarks to Phyllis, as an aide brings him a refreshing drink on a warm day.) This is the point at which the flood of letters from him in the Barker Collection entirely dries up, presumably as an effect of Barker’s death at the end of 1984. On August 22, 1986, The News of Colorado Centennial Country runs a huge feature article on him, under headlines like Mystery man offers death bed statement and Allende trained by Einstein on invisibility theory. A sequel, the week after, is headlined Allende was Colonel in Polish Home Army.

Both articles are written by one Jim Frazier, and are reproduced, though in print so tiny you need a magnifying glass to read them, at the end of Phyllis’s book. (The first has also been made available on the Web by Robert Goerman.) Allende, despite the opening headline, is plainly not on his deathbed. “Carlos said that he feels comfortable in Greeley, as we visited some of his favorite sites. These are his friends. People wave and smile at the bright-minded, colorful old man. He talks to strangers, too; winks at college girls, and flirts with beautiful women. Anyone who has met Carlos seems to remember the friendly, disheveled, out-going man. He speaks in various accents and languages. His Spanish is refined and intelligent. Few people know that Carlos Allende–legally born Carl Allen in Kensington [sic], Pennsylvania, is a mystery to readers and authors all over the world.”

So Carlos is happy at last–well fed, a center of at least modest attention, with plenty of women to “spoil” him and feel their jeans melting in his presence. The gypsy’s wanderings are over; he lives comfortably at Centennial for his eight remaining years. The question inevitably arises: who is paying for all this? Not Carlos himself. Frazier describes him as “nearly penniless,” writes how Carlos puts a touch on him for $10 to mail out copies of a book. (About himself?) It doesn’t seem to occur to Phyllis to wonder about this, although she’s in an excellent position to find the answer, given her daughters’ connections with Centennial. So we are obliged to guess.

And indeed the answer seems obvious: his two surviving brothers, whose names are given in his obituary as David and Richard. (Greeley Tribune, March 8, 1994, reproduced at the end of the book, and on the Web from Robert Goerman’s collection.) Phyllis describes how they show up in Greeley after Carlos’s death to collect his belongings, but vanish before his funeral. This seems at first sight rather callous. It’s possible, though, to read it as an act of love. The last thing David and Richard want is to be put on the spot with questions about their deceased brother, the answers to which are bound to explode the mystery-man legend that gave Carlos’s life its meaning. Their silence, and therefore their absence, is their parting gift to him.

Here’s what I imagine. Sometime early in 1986, starving, sick and desperate, Carlos appeals to his brothers for help. They come to an agreement with him. They won’t send him any money; it’ll disappear, and he’ll be as bad off as ever. Rather, they’ll find a nursing home and pay his expenses there for the rest of his life. His end of the bargain is simply: stay put!

And so it happened; and the best years of Carlos Allende’s life began.

After his death, Phyllis and Ray have plenty of time to speculate on who their friend really was. The theory they come up with is a doozy. When he wasn’t reminiscing about physics lessons with Einstein and bar-stool conversations with invisible sailors–one of which, by the way, inspired “a lady journalist” who was there to write the Broadway hit Harvey (p. 46)–Carlos confided to Phyllis that he’d spent a night talking with Morris K. Jessup, a year or so after Jessup had supposedly committed suicide (p. 67). How was this possible? Because Jessup had managed to turn the tables on a Communist agent who’d been sent to kill him, and the dead man was not Jessup at all, but “the Communist.”

Phyllis and Ray now take this a step further. “The Communist”–whose motives for wanting to kill Jessup are never explained–was the real Carl Allen alias Carlos Allende. And the man they knew as Carlos Allende–was really M.K. Jessup! Jessup, on that fateful night in Coral Gables, had traded identities and identification papers with his would-be assassin. (This is the “hoax” of the title–Allende claiming to be Allende, when he in fact was Jessup.) At last Phyllis can understand why, when she first met Carlos, he looked like he was 90. Born in 1900, Morris Jessup in fact was 90!

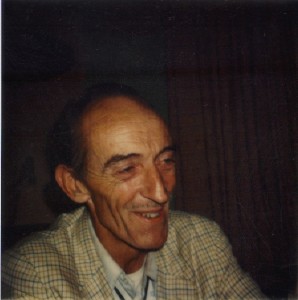

Carl Allen aka Carlos Miguel Allende, 1977 (from the Gray Barker Collection, Clarksburg-Harrison Public Library)

Phyllis’s evidence for this wild notion seems sparse to non-existent, although it’s a little hard to tell, since it’s not presented sequentially but in a series of long conversations between her and Ray. These have the feel of one of those college dorm bull sessions where, at three in the morning and everyone’s eyes bugging out with lack of sleep, a reinforcement loop takes hold and you’re all calling out “Yeah … yeah … YEAH!!!” to the most preposterous suggestions. It would be possible to wish that Phyllis had at least tried to present her ideas in the form of a coherent argument. But this would be to miss the point. Her book is as much a memorial to Ray as it is to Carlos, a testament to the warmth and enthusiasm she once shared with her tragically lost son. She wrote it exactly the way she needed to.

It’s inevitable, then, that the book will leave behind it a trail of minor mysteries. One of these is why both Phyllis and Ray seem to have stayed out of touch with their friend during the last winter of his life. Phyllis visits him early in the fall of 1993; it’s at that meeting, it would seem, that she took the photo of him that she used as the cover of her book. “‘Well, what do you know,’ he said with a big smile as he turned back to me. ‘This is really a nice day isn’t it? It won’t be long till the roses will be gone from those bushes, and the leaves will turn colors and fall, then we will have snow’” (p. 75). Something in his voice makes Phyllis’s throat tighten; months later, learning of his death, she remembers that he didn’t mention the coming of spring, and wonders if he knew he wouldn’t be around for it. That’s the last time Phyllis ever sees him. But the following week Ray takes Carlos to a park for a fast-food picnic, and spreads a quilt for them “in a sun-dappled patch of grass” (p. 76).

“Carlos learned back on one elbow and plucked a blade of grass. Sticking it between his teeth, he looked up at the patches of blue sky peeping between the tree leaves. … ‘That sure is beautiful.’

“He chewed the sliver of grass, tossed it, and reached for another.

“‘You know,’ he said, ‘I used to like to chew grass like this when I was a kid back on the farm. My dad had cattle and hogs, and he used to tease me about eating grass like a cow. Of course, I didn’t really eat it, you know.’

“‘You know’ was a favorite expression of Carlos’s. Ray thought of when he, himself, was eleven and got into the habit of saying ‘you know,’ and had to smile at how I had hounded him and teased him until he finally gave it up.

“Some children played not far away on the little duck, and the car–the small riding toys …. Now, Carlos watched the kids and smiled. He and Roy dozed a bit, speaking little, just enjoying the balmy day and the companionship of a friend.

“‘I could go to sleep right here,’ Carlos said, shaking his head. ‘But I’d better be getting back and take my medicine.’

“Ray helped Carlos to his feet and drove him back to Centennial. It was naptime. It didn’t cross Ray’s mind that day that he’d never see Carlos again.”

For the tenderness of this reminiscence alone, “P. J. Dowers’” book is worth its price.

Reprinted With Kind Permission from This Original Article

Author David J. Halperin can be reached directly by email at david@davidhalperin.net, or on Facebook.