Now the center of various and sundry conspiracy theories, he was once a Fortean.

And because he is the subject of so much speculation, I am trying to be especially careful here. So this post is very long.

Morris Kethcum Jessup was born 2 March 1900 in Rockville, Indiana. I have not seen a birth certificate, but all the important sources agree on this point. (There may not be a birth certificate, either: one of the people to swear out an affidavit affirming Morris’s identity for a passport was the family doctor, who said his birth records had been destroyed by a fire.) Morris’s mother was the former Alice Edna Swaim. His father, George Washington Jessup, was a farmer. Both were native Hoosiers. George and Alice married around 1893; Morris was their first child. At the time of the 1900 census, Theodore Jessup, George’s brother, also lived with the family. There were also several other Swain families living very nearby. Two years later, Morris’s only sibling, Marjorie, was born. (There are some variations in the spelling.) According to the 1910 census, Theodore no longer lived with his brother and sister-in-law. Instead, there were a couple of hands, presumably a brother and sister, Jay Wells, aged 20, who was listed as divorced, and Lollie Wells, aged 18, listed as single. They were Hoosiers, too.

I do not have very much information on Jessup’s doings during the 1910s. According to a later recollection—he wrote this in 1955—Jessup got his first camera in 1913. It was a Brownie. One of the first rolls of films he used was spent taking pictures of a creek that was swollen that year. The Midwest received an unusual amount of rain, and there were large floods. These impressed themselves on his memory enough he would recall them four decades later. Photography would remain a passion, too, at least into the 1920s.

It is interesting to note that the name, Morris K. Jessup, was not uncommon, and was shared even by some rich and famous people, which makes the search for information particularly difficult. Indeed, according to the Des Moines Register has it that Jessup was named for an uncle—last name spelled with just one S, though—who was a railroad baron, banker, philanthropist, and eponym for a Cape in Greenland, since he had financed some polar expeditions. The uncle is also the inspiration for the Iowa town. In addition, there was a Morris K. Jessup at this time who was president of New York’s American Museum of Natural History.

While I have not found military records, there is good reason to believe that Morris served during the Great War. He was of age. And the same Des Moines Register article has him serving in the Navy from 1918-1919. He seems also to have been associated with the Indiana Normal School—later Indiana State University. The school’s 1919 yearbook listed a “Morris K. Jessup” as being involved in the war effort. A few years later, when Jessup applied for a passport, one of those who swore out an affidavit affirming his identity was Cyril Connelly, registrar from that school. Jessup’s attending the Indiana Normal School would explain his presence in the 1920 census; according to it, he was living at home, with his parents and sister, while going to school.

The census taker enumerated the Jessup household on 2 January 1920. Later that year—presumably in the fall—Jessup matriculated at the University of Michigan. The 1920 edition of the “Catalogue of the University of Michigan” lists a Morris K. Jessup from Rockville, Indiana, as enrolled in the Schools of Engineering and Architecture. (There are some indications he may have been attached to the University as early as 1919.) He remained associated with the University for the next eleven years, in various capacities, developing an interest in archeology, astronomy, and engineering. He got married during these years, and the state of Michigan was his home base for a number of long-distance excursions.

In 1921, I think—it could have been earlier—Jessup was appointed an assistant in the astronomy department. He made $200 before resigning his position effective 18 January 1922. The resignation seems to have been because another opportunity presented itself. In December of 1921, he had applied for a passport to visit Guatemala and what was then British Honduras doing archaeological research. He was working with Carl E. Guthe, a professor on the staff, and operating under the aegis of the Carnegie Institute. According to the Carnegie Institution of Washington’s Year Book for 1922, he and Guthe were part of a larger Central American Expedition that explored parts of the Yucatan, northern Peten, and Tayasal.

Jesupp, Guthe, and others sailed from New Orleans to Belize (then British Honduras) on 28 January, probably aboard a United Fruit Company ship. Guthe and Jessup seemed to have done their work independent of the rest of the expedition. Permission was received from the governor of Guatemala’s Department of Peten for their work; they assembled their own team of 12 laborers; and they began work at Tayasal, the last Mayan stronghold on the shores of Lake Peten Itsa, as the report put in, on 20 February. This was the second season of work here. The team dug a number of trenches, locating the eastern and western ends of a structure underneath a large earthen mound. On the eastern end, another trench exposed a cross-section of an even older building.

Guthe wrote that the building—and surrounding city—was probably abandoned around 700 AD, and remained uninhabited for seven or eight hundred years. The accumulation of dirt in the centuries was peculiar, though, covering the south, but not the north. The newer building was then set atop these ruins. Likely this more recent edition was constructed mostly of wood and palm leaf, but there were some stone remnants. Associated with this newer building—based upon the depth—was a skeleton. As there was no skull, teeth, and neither of the top two vertebrae, Guthe assumed the individual had been decapitated. They did find some smaller antiquities—pot shards and the like—but the dearth of them, generally, was striking.

Jessup and Guthe arrived in Mobile, Alabama, on 15 May 1922, aboard the Cibao. The Battle Creek (Michigan) “Enquirer” noted their return to Ann Arbor on 31 May. Jessup was in the University’s General register for 1923, his hometown now listed as Ann Arbor. That year, Jessup was part of another expedition southward. Dr. Carl D. LaRue, a botanist, led a U.S. Department of Agriculture expedition to the Amazon region. I have seen no official documents about this investigation, but it was remembered later by other professors and described in the introduction to an article that Jessup himself wrote for the “Michigan Technic,” published May 1924. At the time, he was listed as in the engineering school, class of 1924. Specifically, according to later reports, he investigated the potential of rubber development in the region. In a later recollection, LaRue wrote that he chose Jessup because of his experience doing photography with Guthe—this was in the Michigan Alumnus Magazine

In the article, Jessup extolled the potential virtues of Amazonia as an agricultural area—palms and rubber trees and nuts grew luxuriously, and trade with the rest of the world was easy thanks to the river and its tributaries. But development was slow, because the people there were not very intelligent and did not know the value of their own country; there was no sense of thrift; taxes were too high; and to this point, the outside world had neglected developing the region—in part because it was just as easy to get the products from home, and in part because the “northern races” “fear tropical life.” All of which to say—the area was ripe for development, and soon there would be a rush, with engineers much in demand. “It will be the engineering type of mind which will solve the riddles of communication, transportation, efficient production, sanitation, immigration and good government.”

Jessup traveled aboard the “Benedict,” leaving Para, Brazil on 8 November 1923 and arriving in New York on 22 November; he soon got back into the fold. According to an article from the January 1925 “Michigan Technic,” Jessup was in the Signal Corps ROTC and, with 12 other Michigan students, attended a training course at Camp Custer—in the state—from 17 July to 28 July. All the travel, though, seems to have slowed down his academic progress some. Nominally part of the class of 1924, he was still a student in 1925, when he was appointed as an assistant in astronomy again, this time for the summer only, it appears. According to the Proceedings of the Board of Regents for the University, Jessup earned $75. He finally graduated with his Bachelor of Science in February 1926, according to the same source.

Also in 1926—according to a later report in an alumnus magazine—Jessup received his Masters of Science. The Colleges of Engineering and Architecture General Announcement for the academic year 1926-1927 noted that he had been made an instructor in astronomy. At the time, he was living on Washtenaw Avenue. The department was small, with two full professors, one associate professor, one assistant professor, and three assistants, including Jessup. It offered eight courses during the year. There was an observatory. In October 1926, W. L. Hussey, one of the full professors, who had reinvigorated the program since the beginning of the 20th century, died, his place filled by his colleague Ralph Hamilton Curtiss.

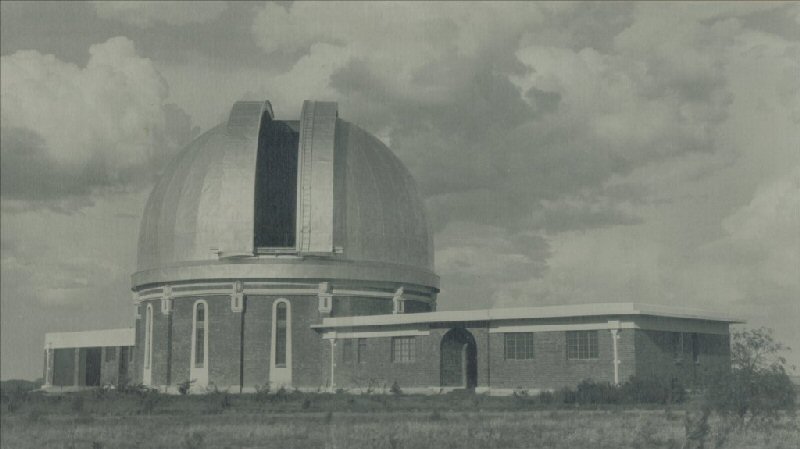

Lamont-Hussey Observatory in Africa 1928

Travel opportunities continued to come to Jessup. Hussey had long nursed the ambition to open an observatory in the southern hemisphere to search for double stars. he had considered both Argentina and Australia before settling on South Africa. In 1927, the Lamont-Hussey observatory opened there, under the control of the University. An observation program began—in earnest, according to a historical overview of Michigan’s astronomy program during the southern autumn of 1928. (The observatory was dedicated 28 April 1928.) Before his death, Hussey had tapped Jessup and another graduate student (Henry Donner) to accompany the new observatory’s chief, Richard Rossiter, to South Africa. Jessup and Donner trained on double-stars in Michigan, then left on 1 October 1927.

All told, Jessup would spend a little more than two years at the South African observatory. (Donner would spend five, and Rossiter would be there until the end of his career, in 1952, finding new sources of funding when the University of Michigan gave up on the observatory in the 1930s.) Between the three of them, the astronomers discovered some 5,650 double-stars by 1930; Jessup, between May 1928 and July 1930, was responsible for 854. For at least part of his time in South Africa, Jessup was accompanied by his wife, Kathryn—probably the former Kathryn Ruth Jones, a native of Indiana, born just a few months before Morris, 7 January 1900. I do not know when they were married. (The Ann Arbor City directory from 1930 does not list Morris as having a spouse, but I do not know when the book was printed.)

Because they were out of the country, the Jessups were not captured by the 1930 census. (Which is too bad because the 1930 census asked if men had served in a war, and could have confirmed he did during World War I.) They returned to the United States on 2 December 1930 aboard the Ginyo Maru. The ship records—and Morris’s later recollections—indicate that they had taken a long, winding route back from South Africa. They had arrived in Los Angeles after sailing from Callao, Peru (leaving 17 November 1930); Jessup’s last astronomical records are from July of that year and The President’s Report to the Board of Regents for the Academic Year 1930-1931 says Jessup left in September, so they seem to have spent some time in South America after—as the ship records mention in a handwritten note—leaving from Johannesburg. The couple listed as their home address the University of Michigan’s observatory in Ann Arbor.

The astronomy program to which Jessup returned had changed. Ralph Curtiss, who had become head of the department just before Jessup left—and who had been a fixture at Michigan since long before Jessup arrived—died unexpectedly on Christmas day 1929 after a short illness. His replacement was Heber Curtis, a Michigan man who was at the Allegheny Observatory in Pittsburgh; the conditions there were poor, and so Curtis had done little research after 1920; an early interest in Einstein’s work had curdled into rejection, and he sided with those who continued to argue that the universe was made of ether. (This older theory was a favorite of Forteans.) Curtis arrived in Michigan in October 1930, just before Jessup would have returned.

Jessup continued his professional astronomical work until July 1931, when he resigned from the department. Funding may have been an issue. The department had been an early victim of the Great Depression, with programs shelved and salaries chopped. It might also be that he was embarking on a Ph.D. program. There are a number of references int he literature to him starting one, but never finishing, and UFO researcher David Halperin has found in the Gray Barker archives some reminisces of Jessup which include him starting the program but not finishing because of personality clashes. His becoming a Ph.D. student explains the Ann Arbor city directory from 1932, which includes Morris and Kathryn, living in an apartment on Elm Street. Morris was listed as a student.

Jessup moved to Iowa and became a professor of astronomy at Drake University no later than the fall of 1932, according to the article, already cited, from the Des Moines register. He was praised for his wide range of experiences and hobbies: he was a photographer (his official position on the Amazon was photographer), radio enthusiast, and pilot. He had plans at Drake: he hoped to open the observatory at night for public lectures and planned a trip to Central America with some students in 1933. I do not know that he ever went on that trip, though. He was in the Drake yearbook as late as 1935—associated with the math club—but I otherwise have no information on the extent of his career there.

One reason for the lack of information about this period in Jessup’s life is that I cannot find him in the 1940 census. He very well may have been out of the country. I also do not see a draft card for him from this period—even older men had to fill them out—but it may have been lost, not yet put into online databases, or he may not have had to do it because he was already associated with the government.

The next information I have on him is from 1942 or 1942—the material from 1942 is speculative, 1943 more definitive. In April 1942, three men associated with The Murray Corporation of America, in Detroit, filed a patent for spring construction. One of the three was a Morris K. Jessup of Grosse Pointe. It should be remembered that Jessup had been in the engineering school and so had some expertise in this kind of work; the depression very well may have had him looking outside academia for a job. So, the area is correct—Michigan—and the form of work, though nothing definitive. Still, the likelihood that he was associated with The Murray Corporation—which was involved with automobile engineering—is increased by his later employment history.

According to “The Rubber Age” magazine, volume 53 (1943) as of 10 June 1943, Jessup was an administrative assistant with the Rubber Development Corporation, which was, despite its name, a government office, at the time under the command of the Office of Administrator of Export Control. Among other things, the Corporation was involved in research in South America. (There are records at the National Archives, but I have not viewed these.) The botany professor Carl LaRue wrote in an essay for the Michigan alumnus magazine, “Eventually his interest in rubber triumphed [over his enthusiasm for astronomy], and he has been for some years a tire engineer for the U.S. Rubber Company in Detroit. That essay appeared in October 1943.

The move to working with rubber seems entirely within character. As early as 1924 he had been thinking that engineers could solve the rubber problem—a problem that was especially acute as America went to war. But even before that, the investigations would have been vitally important to the Detroit area, where Jessup was living. The work probably paid better and was more stable than astronomy, too. Plus, there would be less overnight work. And rubber research would not only engage his engineering muscles, but allow him to travel frequently.

Jessup’s mother died in July 1944 of a cerebral hemorrhage. She was 78. Around this time it seems that Jessup moved to the Washington, D.C area. It may be, indeed, that he kept homes in both Michigan and Washington, D.C., or traveled between the two places. He’s recorded in an air passenger manifest dated March 1947, traveling from Cuba to Miami, which could have been for work or pleasure. (We know it’s the same Jessup because the list also gave his date and place of birth.) The trip had taken about four days. At the time, his home address was listed as 26th Street in Arlington. He was then recorded in a Pan American passenger manifest dated December 1947 , making the same trip. This time he was gone for about a week. His home this time was listed as F Street in Washington, D.C.

Kathryn was not either manifest, which suggests that Morris was, indeed, gone for work; but it may be that she and he were not keeping the same house. Here I take a big, speculative, jump. There is a Kathryn Jessup in the Elkhart, Indiana, city directory for 1947. The middle initial was different—L in the directory, rather than the expected R—but the two letters are easy enough to confuse. This Kathryn was working as a clerk at Conn’s (probably referring to the musical instrument factory.) Kathryn Ruth would later be a clerk, too—which, admittedly, is a stretch, the position common, but worth noting. This period of the Jessups’s life is difficult to track.

Judging by the books that he would write later, Jessup became interested in the occult and paranormal. If this was not an earlier interest—I have no indication either way—he was certainly steeped in the literature by the early to mid-1950s. He read Fate magazine and books on flying saucers. He knew the work of R. DeWitt Miller. He was clearly versed in various forms of Theosophy and its offshoots, including works on Atlantis and Mu, such as those by Ignatius Donnelly. He was in contact with some UFOlogists as well. He also may have been traveling to Mexico at this time to conduct archeological examinations on his own.

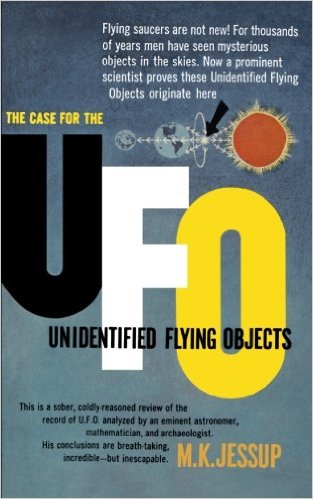

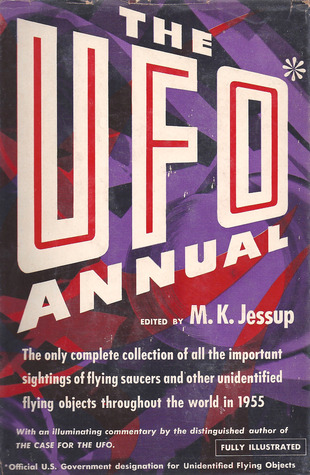

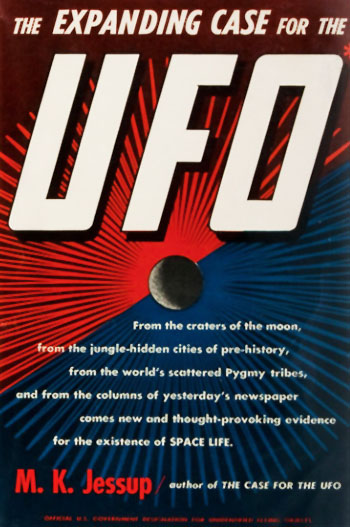

Jessup next came to public attention in 1955, though not to the degree that he hoped. He returned to his enthusiasm for astronomy and took up the subject that had been an American craze—rising and falling, admittedly—since 1947: UFOs. Over a three year span, he wrote four books: The Case for the UFO (1955); UFOs and the Bible (1956); The UFO Annual (1956); The Expanding Case for the UFO (1957). All were put out by Citadel Press, and all pretty much met widespread indifference. Jessup did become part of what John Keel later called “The UFO Subculture,” though, further integrating himself into the social circle, and in later years would become the subject of much speculation for what he did and what he wrote. His completed the first book in Washington, D.C., in January 1955. Frank Edwards, the radio host, Fortean, and mystery monger, wrote the introduction.

Jessup next came to public attention in 1955, though not to the degree that he hoped. He returned to his enthusiasm for astronomy and took up the subject that had been an American craze—rising and falling, admittedly—since 1947: UFOs. Over a three year span, he wrote four books: The Case for the UFO (1955); UFOs and the Bible (1956); The UFO Annual (1956); The Expanding Case for the UFO (1957). All were put out by Citadel Press, and all pretty much met widespread indifference. Jessup did become part of what John Keel later called “The UFO Subculture,” though, further integrating himself into the social circle, and in later years would become the subject of much speculation for what he did and what he wrote. His completed the first book in Washington, D.C., in January 1955. Frank Edwards, the radio host, Fortean, and mystery monger, wrote the introduction.

The first of his quadrology, The Case for the UFO, was a slim book—plumped by long lists and frequent repetition—with grand claims. (According to the copyright notice, the book was published 4 April 1955.) In it, he surveyed a range of various anomalies and united them under a single, unifying theory: human civilization was much older than believed; in the distant past, before some kind of cataclysm, there was a planet-wide culture—like Atlantis or Mu—which developed the power of space flight and levitation. These account for archeological anomalies, such as obviously machined metal in ages before scientists thought such capabilities were possible, and the construction of megaliths such as the pyramids of Egypt. This civilization was either sparked by visitors from space—maybe from the area between Mars and Jupiter—or gave birth to a race of space dwellers.

Either way, there is such an intelligent race, existing in gravitational nodes between the moon and earth. They account for mysterious disappearances of people and machines—kidnappings, research—and also unusual falls—debris from their accidents, from their research, garbage that they dump. For someone who claimed archeological and astronomical expertise, Jessup wrote his book in a colloquial style, wth no evidence of rigorous thought and lots of extrapolation based on the thinnest of evidence—all in the service of supporting what were Theosophical conclusions, though he made no reference to Theosophical literature.

However unconvincing the book was—it sparked a great Fortean mystery of its own. Jessup received two letters from Carl Allen, also known as Carlos Allende, a Pennsylvania drifter. These were typographically bizarre, grammatically unusual rantings. Among other things, they discussed a 1943 experiment by the Navy which caused a ship to become invisible—another possible cause of mysterious disappearances. Jessup seems to have followed up with Allen, but without a great deal of diligence. In time, though, this correspondence would take on a great deal of weight.

Meanwhile, Jessup continued his own research and writing. On 4 June 1956, Citadel Press published his second book, “The UFO Annual.” This was Jessup’s attempt to establish himself—and Citadel Press—as a clearinghouse for UFO information, the center of what he was calling UFOlogy. Already, he noted, he’d received other letters, and some of these confirmed each other, such as independent reports of a spot on the moon appearing 5 July 1955. Despite the name, though, and the ambitions, there were no other annuals. Perhaps he was overwhelmed by the other writing he wanted to do.

Meanwhile, Jessup continued his own research and writing. On 4 June 1956, Citadel Press published his second book, “The UFO Annual.” This was Jessup’s attempt to establish himself—and Citadel Press—as a clearinghouse for UFO information, the center of what he was calling UFOlogy. Already, he noted, he’d received other letters, and some of these confirmed each other, such as independent reports of a spot on the moon appearing 5 July 1955. Despite the name, though, and the ambitions, there were no other annuals. Perhaps he was overwhelmed by the other writing he wanted to do.

Perhaps, too, personal problems intervened. He seems to have been having trouble with his marriage in these years, if not before. According to the Florida Divorce Index, Morris and Kathryn received a divorce certificate—number 4964—from Dade County in April 1956. (Kathryn would remarry in 1964; she passed in 1983.) David Halperin, a UFOlogist who has seen the letter, noted that Jessup told a friend on 3 July 1956 he had remarried. Presumably the marriage took place in Florida—though not necessarily; could have been Indiana—but I have not found any official records confirming the marriage. Morris’s death certificate, though, was signed by a Rubye P., who seems to have been formerly the Rubye Patrick married to Frederick Williams. She was born 9 February 1900 in Mississippi, and would pass 19 January 1978 in Florida.

A few days after he wrote that letter—according to the official copyright notice it was 16 July 1956–Jessup’s third book was published, “UFOs and the Bible.” It was another slim book, barely more than 120 pages—there was less repetition than in his first book, but a great deal of white space. Jessup is more forthright about his Theosophy here: his project, he admits, is basically Theosophical, but more rigorous, Theosophical thought having become unscientific and lax. He wants to unite religion and science, showing the Bible can be understood in scientific terms if read correctly. To this end, he starts with a brief history of Western civilization, showing America is now poised to reconcile science and religion.

The key, he says, is UFOs, which can explain all the miracles of the Bible. And it is no mistake that they are finally being taken seriously now: because we are at the end times. The bulk of the book is an exegesis of Mark Chapter 13 showing that Christ was a soothsayer who predicted the current turmoils and their solution. The Son of Man would return—and in Jessup’s theology, the Son of Man was, of course, the space dwellers who inhabited the region between the earth and moon, sired by some ancient civilization. The Bible—not unlike Nostradamus’s quatrains—was a code that could be deciphered to understand the world’s current predicament and give hope in a time of anxiety.

And there would be anxiety! Some time in early 1957—all the accounts I have read agree on this time table, but I haven’t seen a specific date; likely it was the spring—the Office of Naval Research invited Jessup to discuss an odd development. The Navy itself, in official reports, confirms the general outline of this history. The ONR had received a copy of Jessup’s “The Case for the UFO,” with a number of annotations—done, it looked like on first glance—by three different people, who have since become known as A, B, and Jemi. The commentary suggested that the annotators had knowledge of UFOs and government secrets. Some employees at the ONR, acting on their own, wanted Jessup’s opinion.

He looked through the book, and recognized the writing and references—at least according to later accounts by other writers. I have no sources from the time confirming this. The annotations, he noted, had been made by Allen/Allende. (A 1980 article in Fate magazine seems to have confirmed Allen’s involvement.) By accounts—not very substantial ones, admittedly—Jessup was perplexed; and three navy men were intrigued by what they were reading, thinking there might be clues to important scientific breakthroughs. They financed the publication of Jessup’s books with annotations as well as the letters from Allende. The book was put out by the Varo Manufacturing Company of Garland, Texas.

Apparently at the same time, Jessup continued work on another book—he had mentioned it a few times in “UFOs and the Bible.” It appeared, according to the copyright notice, 6 May 1957. I do not know if this was before or after he visited the ONR, but there was no mention of Allende or the so-called Philadelphia Experiment in the text. The book was relatively long, coming in at over 200 pages, but the first part of it was padded. Jessup repeated topics from his first book—documenting in long lists various anomalous falls. At times, he used the exact same language; at other times, he supplemented the accounts with the results of more recent research, most of it from fringe literature such as Fate. He then left this material behind and essentially wrote three different kinds of books, all between the same covers: it is this diversity that accounts for the book’s length.

The three topics he took up, in order, were, the failure of rocketry; the likelihood that the moon was inhabited; and the source on earth of the UFOs. On the first point, Jessup was unimpressed with rocketry as a mode of space travel—true space flight needed to manipulate the laws of gravity, as he thought UFOs did. Rocketry was minor, perhaps launching things into the space between the moon and the earth, but otherwise “silly”. Indeed, he thought humans had mastered greater technologies in the past, and suspected that all the talk of satellites at the time was just a prologue to America announcing the Soviets had already launched a satellite years before.

The three topics he took up, in order, were, the failure of rocketry; the likelihood that the moon was inhabited; and the source on earth of the UFOs. On the first point, Jessup was unimpressed with rocketry as a mode of space travel—true space flight needed to manipulate the laws of gravity, as he thought UFOs did. Rocketry was minor, perhaps launching things into the space between the moon and the earth, but otherwise “silly”. Indeed, he thought humans had mastered greater technologies in the past, and suspected that all the talk of satellites at the time was just a prologue to America announcing the Soviets had already launched a satellite years before.

Jessup then moved on to the moon, which had been the object of his fascination from the first book, He was sour in the idea of interstellar travel—he knew, from his astronomical research—that the distances were too vast to be covered. The source of the UFOs had to be much closer: the moon. He mounted a case for the moon being inhabited, possessing ice and an atmosphere, perhaps even vegetation. He pointed to the presence of unusual lights on the surface as evidence of something operating there. Perhaps in time there had even developed a race of giants—grown large because of the moon’s weak gravity.

But, if so, that race had started out very differently. In the last section, Jessup turned to ethnology—the book, after all, was a combination of Fortean anomalies, with astronomical and anthropological speculations (he called them hypotheses). Jessup noted that many reports had flying saucer inhabitants as little, and this fact got him thinking. Perhaps the space faring race that inhabited the area between the moon and the earth had descended from pygmies. Perhaps these small humans had developed the technology necessary to reach space in the distant past, that knowledge then lost during some great cataclysm. The remainder of the book was him canvassing various anthropological reports and cherry-picking data to support his contention. “The Expanding Case” ended abruptly, with a half-page epilogue but no conclusion.

Reports have it that Jessup became increasingly depressed through 1957, marital problems, his dealings with the navy, and the failure of his books to find a wide audience. (He had stopped corresponding with Gray Barker, it seems, in January of the year.) I have no contemporary evidence of these claims, though. It is worth noting, too, that the Russians did launch a satellite in October 1957—not before, as he had it—and with it in orbit came no evidence of his theories. Sputnik was followed by Sputnik 2 the next month. Then came the U.S.’s Explorer 1, Vanguard 1, Explorer 3; the Soviet’s Sputnik 3; and the U.S.’s Pioneer 1—all within the next year. By October 1958, it was getting crowded in the space between earth and the moon, and no support for any of Jessup’s hypotheses. Rocketry was working; his paranoia about government disinformation wasn’t holding up; no satellites were running into UFOs.

At some point, Jessup moved back to Indiana, whee he edited an astrological publication, according to fellow Fortean and UFOlogist Ivan Sanderson. (Note that Sanderson’s recollections are often unreliable.) I have found no sign of this publication. Other sources have him attempting to make another trip to Mexico but failing—but they are also uncorroborated. He visited Sanderson’s home in New Jersey around October 1958. Jerome Clarke—a friend of Sanderson’s—wrote that at the time Jessup “was deeply depressed [and] he intimated that he might not live much longer.” Sanderson’s own account—from a decade later, September 1968—was more paranoid. Jessup was overwhelmed by the stage things happening to him worried he would be accused of insanity (which would then reflect on his grandchildren) and suggested that something might happen to him.

Still according to Sanderson, Jessup was supposed to return home, but instead one to New York on business, then, for some reason, to Florida, where he re-opened his house there. While in Florida, he was hurt in a serious car accident, which pushed him into a deep depression: he had been unable to do any work since the accident and was upset that he’d become a vegetable. Sanderson interpreted a letter Jessup wrote to a friend at this time as a suicide note. Sanderson thought that Jessup had been depressed for depressed for over a year, mostly because publishers had rejected his recent manuscripts as not being up to his previous standards. Probably, he suspected, it was the Allende case which had precipitated this fall—he’d become distracted and doubting since it.

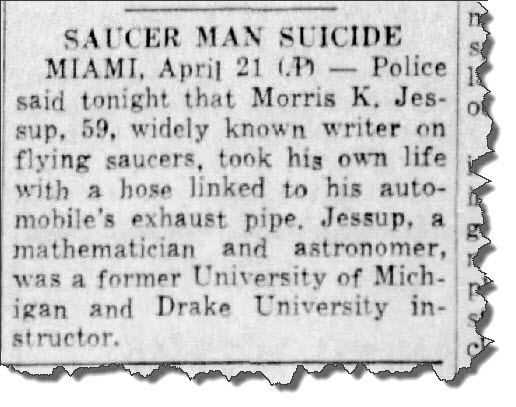

On April 20 1959, around 6:30 in the afternoon, Morris K. Jessup was found in his station wagon at Dade County Park. (Sanderson would wrongly say he was not found in a park, but a garage.) He had poisoned himself from the car’s exhaust. Jessup was a month past his 59th birthday. In death, he became more famous than when he was alive.

On April 20 1959, around 6:30 in the afternoon, Morris K. Jessup was found in his station wagon at Dade County Park. (Sanderson would wrongly say he was not found in a park, but a garage.) He had poisoned himself from the car’s exhaust. Jessup was a month past his 59th birthday. In death, he became more famous than when he was alive.

The so-called Varo edition of his book had been published in a very limited edition. But in 1962, Fortean N. Meade Layne’s Borderlands Sciences Research Association published the annotations to the monograph “M.K. Jessup and the Allende Letters.” (Jessup had been in contact with the BSRA earlier and approved of their interest in UFOs, though he and the BSRA had very different ideas about the nature of flying saucers.) The following year Gray Barker published “The Strange Case of Dr. M. K. Jessup.” Another two years on and Fortean Vincent Gaddis spent a chapter on Allende and Jessup in his book “Invisible Horizons.” Sanderson took it on in 1967’s “Uninvited Visitors.”

Jessup continued to be entwined with the Borderlands Science Research Association after his death, too. A 1974 volume of the Journal of Borderland Research printed reports of his post-death research, as channeled through a medium. The Association argued that Jessup was a victim in a war over the control the planet and those who would control it. His report—again, through a medium—confirmed the apocalyptic nature of the era, and also the BSRA’s approach to flying saucers. (The seance was done under the aegis of Gray Barker, around 1963.) According to the BSRA’s account, Jessup claimed that flying saucers were etheric—they traveled through different dimensions by changing their density—and his astral self had been taken to Venus after his (still mysterious) death. The point of the saucers was to expose humanity to the occult truths of the deity.

By this point, the story was becoming a classic in the Fortean literature, repeated in ever more texts through the 1970s explosion of fringe literature and into the 1980s. Jessup’s own theories no longer stood up at all: humans had walked on the moon. The space between the earth and its satellite had been explored. There was no race of intelligent beings living there. But it hardly mattered anymore. The suggestion was made that he knew something—some government secret. His death was ruled suspicious, attributed to malevolent forces, probably official. It was the stuff of conspiracy theorizing and speculations increasingly divorced from the facts, a free-floating example that the powerful were in possession of tremendous scientific secrets and would result to murder to protect them. At this late date—almost sixty years after Jessup died—it’s unclear what those secrets could be, but by now Jessup has gone from Fortean to Fortean anomaly.

Jessup’s story reminds us of how much Fortean activity could take place beyond the realm of the Fortean Society, especially regarding topics that Tiffany Thayer did not credit. He disliked flying saucers a lot—he thought that they made true Fortean research difficult, as every aerial anomaly was interpreted as a flying saucer, and the entire story garbled by the press. It was pablum for the people, a way to keep them from seeing the real goings-on in the world, Nor was Thayer particularly inclined to Theosophical musing; especially as the 1940s gave way to the 1950s, there seems to have been much fewer mentions of Theosophists or their ideas in the Fortean Society magazine Doubt. Jessup, of course, combined Theosophical speculation with flying saucers, and so was very likely to be ignored.

His name started appearing in Doubt more than a year before his first book was published, and continued for only a short time. All told, it appeared five times between February 1954 (Doubt 43) and August 1955 (Doubt 49), inclusive. But each mention was only a generic acknowledgment in a long list of credits. Indeed, it is entirely possible that the reference was not to Morris K. Jessup, the UFOlogist, at all, since the citations consisted only of a surname—and Jessup was a common enough last name. Very likely, though, this is the same Jessup, Morris K. Jessup, because his books are very clearly influenced by Charles Fort.

I cannot say exactly when Jessup first came to Fort or the Fortean Society. The years after he left Drake University and before he wrote his first book are too little known. At some point he must have started reading Theosophical, or related literature—he mentioned Ignatius Donnely, for example, and shows a knowledge of theories about Atlantis and Mu. The degree to which Theosophy—and Fort—shaped his thinking (and writing) certainly suggests a long acquaintance: both come through in the tests much more than his archeological and astronomical knowledge, which seems amateurish, never mind that he did professional work in both. The man who wrote “The Case for the Flying Saucer” and the other three books had clearly read and taken in Fort. And by the time of his last book, he was also plumbing “Doubt” for information.

“The Case for the UFOs” is principally a Fortean book: it is concerned with all sorts of anomalies, beyond flying saucers. Jessup makes a rough division in these anaomalies, between material ones and spiritual ones, and says that he will focus on the material—nothing on the afterlife or mediumship, then. The material oddities—a word he uses often, along with erratics, both of which suggests he had read Rupert T. Gould—he divides into three categories. These are basically Fortean: strange falls, mysterious disappearances, and unusual astronomical phenomena. The book then unites all of these via flying saucers. At heart, Jessup is a Fortean monist: “Our solar system as one living entity. This war-weary, heartsick and bedraggled planet is not alone—it is just one cell in a multicellular unit.”

The language, arrangement, and material all borrow heavily from Fort and Forteans. Many of the chapters are essentially long lists of unusual occurrences which he has obviously culled from the Fortean literature. (He does cite Fort at least once.) He uses me of Fort’s favorite sentence structures—rather than the Fortean “It is our expression” we have the Jessupian “It is our suggestion.” The various anomalies are then stitched together into a giant theory. Even seemingly disparate classics of the Fortean literature are woven in. For example, he makes a great deal of the Devonshire devil’s hoofprints, which, on first blush, seem unconnected to flying saucers. But for Jessup they are an example of a mysterious disappearance.

Jessup’s sources are generally more problematic than Fort’s. He relies on “Fate” magazine a lot—another sign he’d been reading the fringe and occult literature—as well as mass-market magazines “Look” and “Collier’s” (which ran R. Dewitt Miller’s articles). He points to other Fortean writers—Leslie and Adamski, H. T. Wilkins, Kenneth Arnold (as well as the older Ignatius Donnelly). He refers to correspondence he had with Miller. Some of his off-hand conclusions are reminiscent of other Forteans. He says that people should not worry over much about flying saucers; they have been coming to the earth for a long time, and so do not represent a new threat (perhaps they are even here to warn us away from flying saucers, he says). This echoes an idea by Marcia Winn, who similarly wanted to de-couple flying saucers from national security concerns.

The basic story that Jessup tells in this book is a mixture of Theosophy and Fortean ideas. He argues that flying saucers do not come from deep space, or even other planets—the distances are just too vast; rather, they originate in the area between the moon and the earth: a reworking then of Fort’s New Lands, which had the galaxy much smaller than astronomers thought. This race of beings is responsible for the strange falls—detritus, he said, from their work and, perhaps, accidents. Which, of course, is merely Fort’s Super-Sargasso Sea with a different name. The mysterious disappearances are caused by these same space dwellers collecting humans and animals and ships for experiments—like Fort’s Ambrose collector. Perhaps we are property, then, fished for at the bottom of the space-ocean. The actions of these space dwellers—generally friendly, if much advanced of our own species—accounts for astronomical anomalies such as weird lights on the moon and obscure spots on the sun.

The origin of these creatures is pure Theosophy. Jessup argues that once, long ago, there was a world-wide culture on earth that developed space flight and levitation. We know this from out-of-place antiquities—ancient rocks that show the action of human machines—the inability of ancient engineering techniques to account for monoliths such as the pyramids, and esoteric theories about Atlantis and Mu. Perhaps, Jessup says, this ancient culture was brought from space; or perhaps it gave rise to the space dwellers. At any rate, some worldwide cataclysm destroyed most of it, cutting humanity off from the space dwellers, and forcing human to re-evolve a technological civilization—though some techniques remain lost, principally the control of gravity, which allows for levitation and true space flight. He ended his book with a Fortean call, though: tasking readers to go through old books and records looking for evidence to support this thesis.

Jessup’s second book, “UFOs and the Bible,” similarly mixies Fortean and Theosophical speculations, though to different ends. In it, Jessup cites Fort by the first page, as he is taking shots at science—but not religion. He wants those skeptical of flying saucers to recognize that UFOlogists are not undoing Christianity, but rationalizing and substantiating the Bible in light of modern science. He notes that Fort did not extend his research to the Bible, but he will—and so Jessup’s task is again essentially Fortean, extending it in a new direction. A later chapter titled “Moses and Charles Fort” looks explicitly for Fortean phenomena in the Bible. His thumbnail sketch of Western history is more Theosophical than Fortean—he finds a dialectic, with science and religion coming together, as Theosophists did, rather than a transcendence of both religion and science int he era of the hyphen, as Fort did—but there remain echoes. He is not entirely sure of Theosophical speculation, arguing it is too lax and unscientific, as opposed to the Fortean method.

In the end, though, the book again reveals a Theosophical foundation. Jessup casts Immanuel Swedenborg, Ur-source of Theosophy, as in communication with the divine—his ascended masters were the flying saucers, giving him an understanding of the occult forces that shape the earth and human history. His apocalyptic reading of Matthew, which takes up the bulk of the book, is similarly Theosophical in approach, of not Gnostic. He is reading the Bible as an esoteric code, one which has to be interpreted in light of history’s unfolding. The Son of Man all return—in a spaceship. And soon.

“The Expanding Case for the UFO,” the final book in Jessup’s series, owed little to Theosophy and, instead, took on the cynicism of Tiffany Thayer, while also remaining rooted in Fort’s earlier, less weary, ideas. After a gnomic fable opening the book, Jessup recapitulated the argument from his earlier book, batted away critics by saying he was not jumping to conclusions but making hypotheses, which scientists are supposed to do (Sanderson made similar kinds of arguments), name-checked the BSRA, and then repeats large chunks of his first book, both in structure and the exact language. There are additions, though, some of them cribbed from Doubt, though not all sourced. He mentions the ice falls in Long Beach reported by Dulcie Brown, for example, but does not cite Doubt. But then explicitly does acknowledge that magazine as the source for other bits of data. Fort is cited, as are other Forteans—such as W. L. McAtee, who, it seems, Jessup discovered through Doubt.

In addition to citing Doubt, Jessup borrows some of Thayer’s rhetorical tricks. He dismisses work on rockets and calls plans to send up objects that could orbit the earth “silly satellites,” a locution that is reminiscent of something Thayer might write, and not like anything in his earlier books. He has a paranoid view of the press and governments that also reflects Thayer’s and nothing in his earlier writings. He suspects the government and press of working in cahoots to either prepare the world for an announcement that a UFO has been captured—perhaps by the Russians—or that the Russians had already launched a satellite years before, and was spying on America. He thought focus on rocketry was mis-placed, and suspected the Russians might be doing better space research than Americans because they had reverse-engineered the gravitational control systems of the space dwellers from a UFO.

The book then ended with a long disquisition suggesting that the ancient humans who gave birth to the space dwellers—this was his strong hypothesis now, more likely than life on earth coming from the stars—were much like the modern-day pygmies. The racial essentialism is more than a little disquieting to modern ears—though it fits with Jessup’s earlier writing on rubber development in the Amazon—but it does, broadly speaking, fit with Theosophical theories about a succession of races having dominion over the earth. Theosophists note that these different rot races—as they are called—have different physical characteristics, some tall and lean, some short, some barely matter at all. In Jessup’s system, the earlier race, the one that covered the earth and mastered levitation as well as space flight—were short and stout, like the pygmies. And this is why so many people who claim to have seen flying saucer inhabitants remark that the space fellows are “little people.”

As far as I can tell, Jessup’s Fortean thoughts have not survived very well. Given the number of satellites humans have launched and the visits to the moon, it has become impossible to argue that there is a race of space dwellers inhabiting the region between the earth and the moon. (Unless, like the BSRA, one also contends that these beings can control their density and move from dimension to dimension.) Fish falls cannot be explained by dumped hydroponic tanks—as Jessup did—nor rains of metal by crashes between space freighters.

There are echoes of his ideas, though, that do persist. The idea that humans are collected for research—a Fortean idea—is reflected in accounts of alien abductions and cattle mutilations. Mysterious disappearances and the great, ancient monoliths still attract explanations that rely on the intervention of space beings. Jessup, of course, is not the sole source of these ideas, but he is one source.

Mostly, though, Jessup is remembered himself as a Fortean phenomena. His biography is not complete, and had to be put together by pieces. His connections to the rest of the Fortean community remain—at leas to me—relatively obscure. That anyone in the government should pay him the least heed raises eyebrows. The Allende brouhaha only deepens the strangeness. It is all explicable, of course, but it is also all very weird. And then there is his death. It fits too well a cast of mind that is on the look out for grand government machinations, for covert operations, for esoteric meaning in mundane actions—meaning that can only be extracted by proper reading, with the right code for deciphering.

Reprinted With Kind Permission from This Original Article

Author Joshua Buhs can be reached directly by email at joshuabbuhs@gmail.com, or on his website

Morris K. Jessup

“You must remember that he was not a ‘crank’ writer, but a distinguished and famous scientist.”

Dr. J. Manson Valentine

“If he committed suicide, it was probably due to extreme depression… He was also despondent over the criticism directed against his books by the scientific and academic world.”

Dr. J. Manson Valentine